This document provides a structured, educational, and visually guided overview of using PHA biopolymer and FDM 3D printing for coral reef restoration. It includes explanations, workflows, use cases, design guidelines, and image references.

1. Introduction to PHA Biopolymer Heading Text Here

PHA (Polyhydroxyalkanoate) is a naturally occurring bioplastic produced by microorganisms. It is fully biodegradable in marine environments, making it a promising material for reef restoration.

PHA is recognized and consumed by marine bacteria, breaking down into CO₂, water, and microbial biomass. It does not create microplastics and biodegrades safely in the ocean.

2. Why PHA for Reef Restoration?

From a materials-science and marine-ecology perspective, PHA occupies a unique space among polymers used in the ocean.

2.1 Chemical Nature

Polyhydroxyalkanoates are a family of intracellular polyesters synthesized by bacteria as carbon and energy storage. The most common variants used for filament are:

- PHB (poly(3-hydroxybutyrate))

- PHBV (poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate))

Structurally, these are long chains of hydroxy–fatty-acid monomers linked by ester bonds. In seawater, these ester linkages are highly susceptible to enzymatic hydrolysis by PHA depolymerases secreted by marine microbes.

When PHA degrades, the polymer backbone is cleaved into soluble monomers and oligomers such as 3-hydroxybutyrate (3HB) and 3-hydroxyvalerate (3HV). These are low-molecular-weight organic acids that are already part of natural marine carbon cycling and can be readily metabolized by heterotrophic bacteria.

2.2 Biodegradation Pathway in the Ocean

In a reef setting, the life cycle of a PHA scaffold typically follows this sequence:

- Biofilm Formation – Within days to weeks of immersion, the PHA surface is colonized by bacteria, microalgae, and other microorganisms forming a biofilm. This conditioning film modifies surface chemistry and roughness, often increasing larval settlement potential for corals and invertebrates.

- Enzymatic Depolymerization – Specialized PHA-degrading bacteria express extracellular PHA depolymerases that attack the polymer surface. These enzymes cleave ester bonds, releasing 3HB/3HV units into the boundary layer.

- Uptake and Mineralization – Neighboring microbes use these monomers as dissolved organic carbon. Through central metabolic pathways (e.g., β-oxidation and the TCA cycle), the carbon is converted into CO₂, H₂O, and microbial biomass. This is termed complete mineralization and leaves no persistent microplastic residue.

Structural Weakening – As depolymerization proceeds from the surface inward, mechanical properties decline. In practice, reef structures maintain functional integrity for months to a few years, then gradually fragment and disappear, leaving coral skeletons and calcareous epibionts as the dominant physical structure.

2.3 Ecological Fit for Reef Work

Compared with conventional thermoplastics (PLA, PETG, ABS, nylon), PHA offers several advantages in a coral-reef context:

- True Marine Biodegradability – Degradation is driven by in situ microbial consortia under ambient seawater conditions, not by industrial composting.

- Benign Degradation Products – 3HB/3HV and derived metabolites function as substrates in the microbial loop rather than pollutants.

- No Long-Lived Microplastics – The material is designed for full mineralization, avoiding accumulation of persistent fragments in reef sediments or biota.

- Compatible with Biofouling and Settlement – Early-stage biofilm formation and surface roughening can enhance coral larval settlement and invertebrate colonization, turning the scaffold into a biologically active microhabitat.

For reef restoration, this makes PHA an ideal candidate for sacrificial scaffolds: structures that provide engineered geometry and stability during the critical early years of coral growth, then phase out of the system without leaving synthetic debris.

3. Biodegradation Cycles of PHA in Marine Environments

The degradation of PHA in ocean settings is not a simple breakdown—it is a staged ecological process involving microbes, biofilms, enzymatic action, and nutrient cycling. Each phase provides unique benefits for coral restoration.

3.1 Stage 1 — Biofilm Conditioning Layer

Within hours to days of immersion, marine bacteria, diatoms, cyanobacteria, and microalgae colonize the PHA surface, forming a conditioning biofilm.

Ecological benefits:

- Creates biochemical signals that attract coral larvae.

- Increases surface roughness, improving settlement likelihood.

- Begins the “biological handoff” from engineered material to natural processes.

3.2 Stage 2 — Enzymatic Depolymerization

PHA‑degrading bacteria secrete extracellular PHA depolymerases, cleaving ester bonds in the polymer backbone. Long hydroxy-fatty-acid chains become 3HB/3HV monomers.

Ecological benefits:

- Releases biodegradable organic carbon that feeds microbial communities.

- Encourages growth of heterotrophic bacteria involved in nutrient recycling.

- Promotes early-stage ecological succession on restoration sites.

3.3 Stage 3 — Uptake & Microbial Mineralization

Microbes metabolize 3HB/3HV monomers via β‑oxidation and the TCA cycle.

Final products: CO₂, water, microbial biomass.

Ecological benefits:

- No microplastic formation.

- Supports the microbial loop that drives reef productivity.

- Leaves behind coralline algae, calcifiers, and coral skeletons as the persistent structure.

3.4 Stage 4 — Structural Softening & Ecological Replacement

As the scaffold weakens, it becomes fully integrated into the benthic community.

Ecological benefits:

- Coral and calcareous organisms take over physical structure.

- PHA disappears without cleanup, lowering diver workload.

- Transition from man‑made to living reef is seamless.

4. Benefits to Marine Biologists & Reef Restoration Labs

PHA-based 3D printing offers powerful practical advantages for scientists, restoration teams, and field operations.

4.1 Design Freedom for Experimental Research

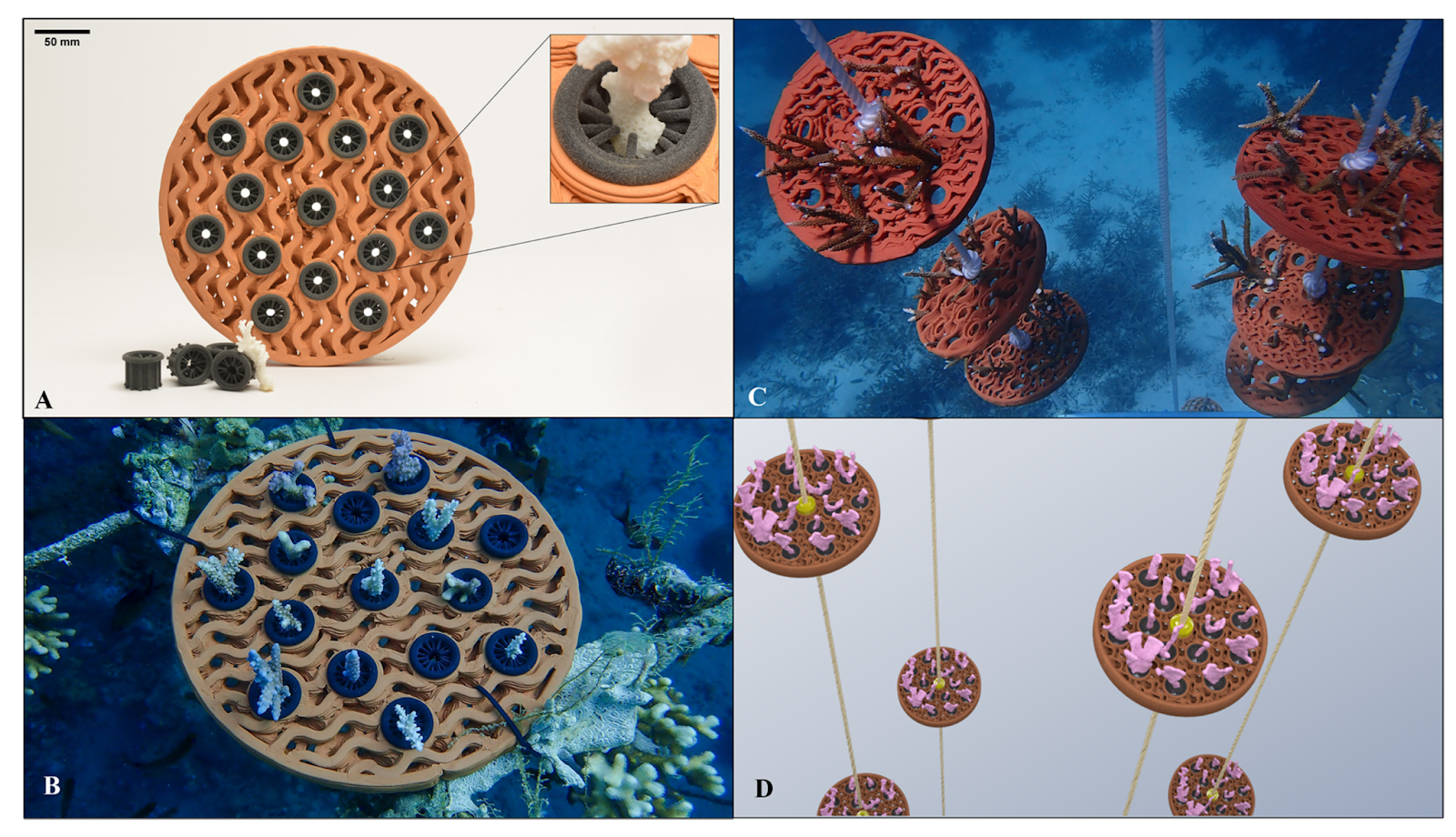

Researchers can prototype substrates, cages, tiles, racks, and geometries that target specific questions:

- Which microtextures improve larval settlement?

- How do branching structures affect flow and light exposure?

- Does substrate complexity change species recruitment patterns?

With 3D design tools, biologists can test hypotheses in hardware instead of relying on fixed, traditional materials.

4.2 Precise, Repeatable, Controlled Geometry

Traditional restoration materials (concrete, rubble, PVC) are inconsistent. PHA printing ensures:

- Consistent thickness, porosity, and texture.

- Controlled variables for scientific experiments.

- Replicable data across deployments.

4.3 Reduced Labor & Long-Term Maintenance

Because PHA biodegrades naturally:

- No retrieval dives are required to collect decayed structures.

- Teams avoid leaving plastic waste on reefs.

- Scaffolds protect corals when young, then vanish once no longer needed.

This is a major operational advantage for restoration labs with limited dive hours.

4.4 Environmentally Safe “Sacrificial” Structures

Labs can deploy structures designed to:

- Last only during the critical growth phase.

- Disappear as the ecosystem reclaims the site.

- Leave no synthetic residue or microplastic pollution.

4.5 Faster Deployment Cycles

Researchers can:

- Design → print → deploy within days.

- Rapidly iterate tile shapes or protective platforms.

- Scale production using print farms (like Bambu systems).

This accelerates restoration experiments and field testing.

4.6 Education, Outreach & Funding Alignment

PHA aligns with:

- NOAA and UN sustainability goals.

- Donor interest in biodegradable technologies.

- Public outreach messaging about regenerative restoration.

It becomes easier for labs to secure grants when using modern, eco‑positive materials.

5. FDM 3D Printing With PHA

Printing PHA is similar to PLA with slight adjustments.

Recommended Settings

- Nozzle Temperature: 195–205°C

- Bed Temperature: 55°C

- Cooling: 50–70% after first layers

- Perimeters: 4–5 walls

- Infill: 40–60% gyroid

First Layer Speed: 20 mm/s

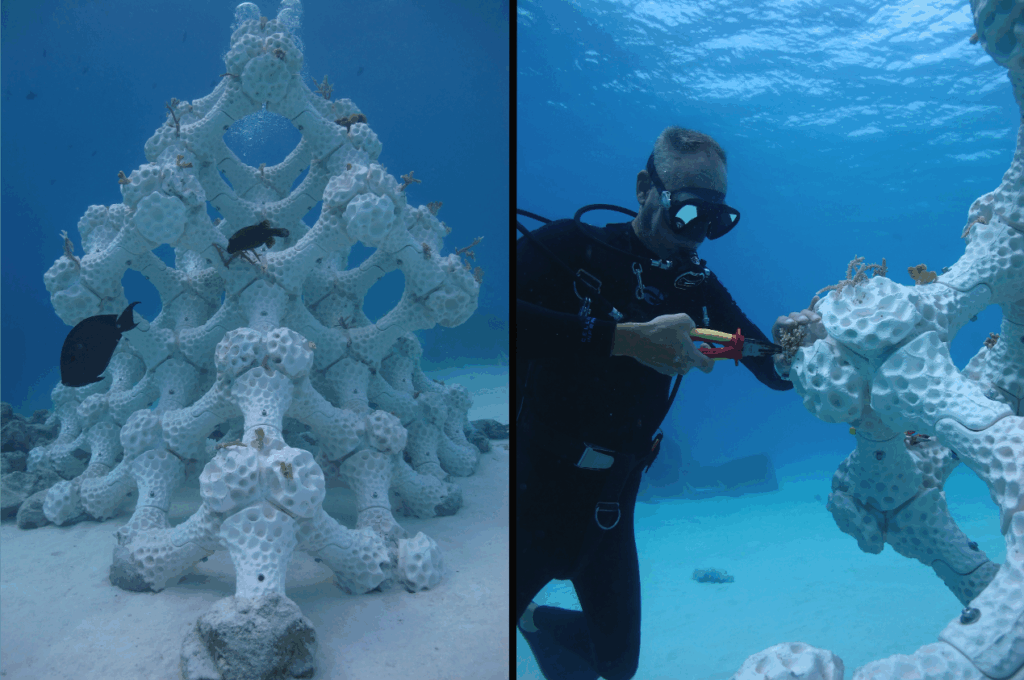

6. Applications in Reef Restoration

6.1 Reef Tiles

Flat or textured tiles that serve as substrates where coral larvae can settle and grow.

6.2 Coral “Branch” Structures

Elevated forms designed to optimize water flow and light, aiding coral fragment growth.

6.3 Protective Cages

Temporary protective housings for young corals, designed to biodegrade as the coral matures.

6.4 Coral Nurseries

Structures used for growing coral fragments in controlled environments before out-planting.

7. Protective Cage Design Considerations

- Modular, open mesh structures

- Stainless steel or rope anchor points

- Designed to degrade over time

- Provides shelter while corals are vulnerable

8. Study Summary

PHA-based 3D printing brings a sustainable, biodegradable approach to reef restoration structures. By combining 3D design creativity with texture modeling, PHA Material, and careful print settings, you can design:

- Reef tiles

- Coral scaffolds

- Protective cages

- Nursery fixtures

All of these are designed for temporary use, leaving behind natural mineral coral growth rather than plastics.

This creates a fully regenerative, sustainable cycle: print → deploy → protect → biodegrade → leave coral behind.

For more information on how to take the next step with us, send an email [email protected]